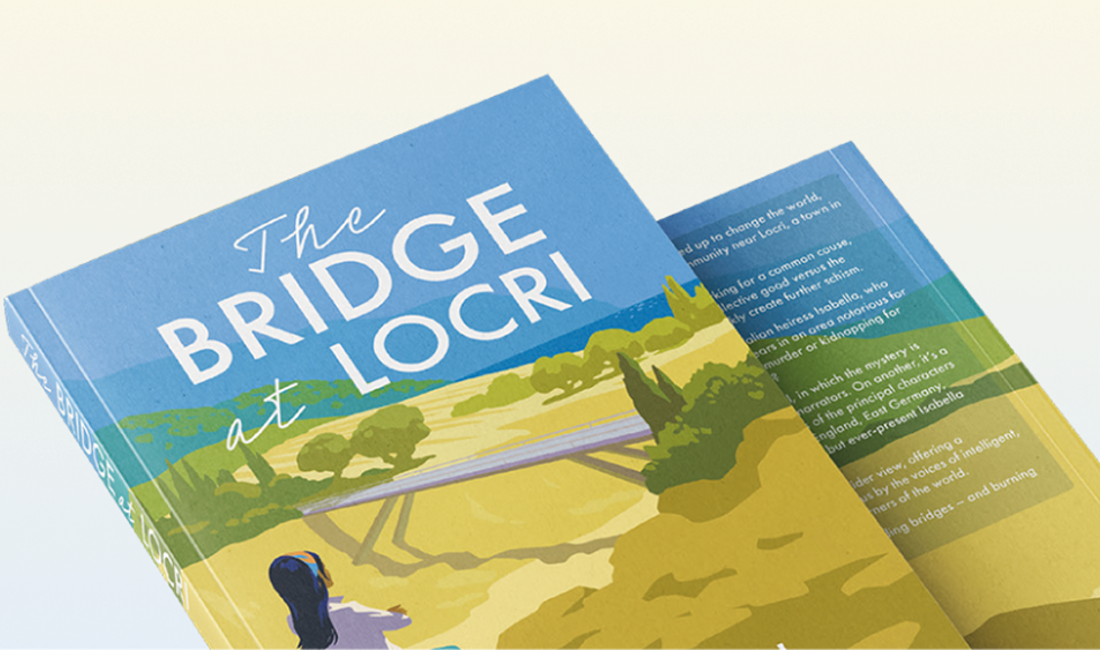

The new book tells the story of a group of pacifists who come together in 1963 to build a bridge across a valley in Locri, Calabria, a small town on the Ionian coast of Italy, an area notorious for the ‘Ndrangheta mafia. The touch paper is lit when one of the volunteers, beautiful heiress Isabella, from Rome, who has been having affairs with two of the volunteers, mysteriously disappears. Has she been murdered or kidnapped for ransom?

This question remains unanswered for 60 years. In the meantime, all the other main characters, who come from England, East Germany, Bosnia, Australia and Colombia, face the challenges of life in their own countries, each badly affected by Isabella’s disappearance, which looms large throughout the book. The Bridge at Locri is both a mystery and a social history of our times.

At the London launch our own talented Colin Miller shot a video of the London launch, the interview with Mark conducted with a great deal of professionalism by Debroah Arthurs, the editor of Metro. We are fortunate to have in the company, project manager and our books ‘guru’, Angela Shaw, who is from Calabria. At the London launch Angela provided telling insights into the beautiful region of Calabria. The only real element of truth is that Mark was a volunteer at the workcamp in Locri in 1963 and rediscovered the bridge The rest of the book is pure invention and fiction.

Below is an excerpt from the book:

The first time I clapped eyes on Isabella she was pushing a wheelbarrow full of concrete and shouting profanities at Maestro Pedro. It was July the 19th, 1963.

“Questa è merda!” she exclaimed before switching to flawless English. “This is shit! There’s too much water in the mix and not enough sand.” She banged on the wheelbarrow, mixing the two languages. “And bugger this carriola, it’s too hot to work.”

Whether Maestro Pedro completely understood her was not clear, but he paused and smiled benignly. Her rant suddenly over, Isabella started to push the wheelbarrow for several yards before tipping its contents into an excavated area which would form part of the approach to the bridge.

Isabella was one of those people you see once and never forget. She was straight off a film set, completely at odds with her current environment. She was the epitome of classical beauty with a tanned face of perfect symmetry, her long, thick, dark locks falling down her back. Despite the heat and the dust not a hair seemed out of place. She was slim, about five-foot-seven, wearing sleek blue jeans and a white top. Her dark eyes sparkled in the hazy, late afternoon sun with a sense of bewilderment and fun. Despite her glamorous appearance she was obviously well able to push a wheelbarrow around.

To say that Isabella made an immediate impression on me is a complete understatement. It was like being hit by a tidal wave of possibility, adventure and expectation. Here was I, a country boy straight out of boarding school, confronting for the first time the most extraordinary woman I had ever seen. It is simply not true to say that people do not fall in love at first sight. Not true for a second. I was captivated in a way that I’d never imagined.

Now she turned and spotted me, eyeing me with amusement. “You the new English guy? I hope you have brought your bloody tea with you. Tea. Tea. Tea. That’s all you English think about, isn’t it?”

She did not wait for an answer before turning to her more heavily built and shirtless companion. “This is Maestro Pedro. He’s the one professional worker we have. The rest of us are a bunch of amateurs trying to work it out.”

“And beer,” I said, shaking Maestro Pedro by the hand.

“What’s birra got to do with it?” she asked.

“Nothing, except you said that we English only think about tea. We also think about beer as well. And I could do with one right now.”

“Sei un po’ avanti. You are a bit ‘forward’ — I think that’s the word — for a young boy. You come to Calabria and the first thing you ask for is a beer. Next thing you will be asking for is a . . . I won’t say it, but the word begins with an F. How old are you?”

“Nearly nineteen. And you?”

“You never ask an Italian lady her age, but let’s say that I am six years more grown up than you.”

“You speak such good English.”

“Thank you, but you’re teasing me. I make lots of mistakes. I studied English at university in Rome and spent a few months in your cold and wet country in a place near London called Bromley.”

“I have heard of it, but I come from a small town called Castle Cary in deepest Somerset.”

“Zummerzet,” she said, with a good attempt at mimicking the accent, “where the zider apples grow.”

“Spot on,” I replied, “You seem to have a much better grasp of England than I do.”

“If you had said Yorkshire, I wouldn’t have had a clue, but I went on holiday for two weeks in Wells — what a lovely cathedral — so I know a tiny bit about your county. And I had an English friend who came from Shepton Mallet in Somerset and I stayed with her and her family on one or two occasions and they would take me to the pub to drink cider. So there you go.”